Beowulf as Picture of Post-Pagan, Pre-Christian Culture.

How Beowulf highlights a people in flux.

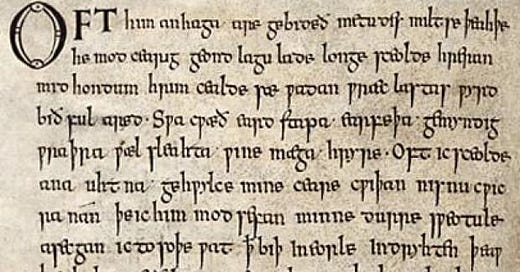

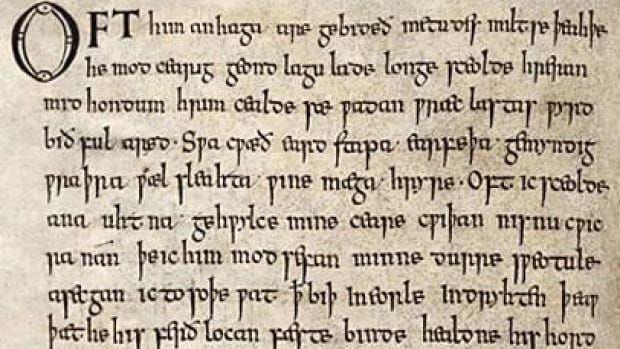

The epic poem Beowulf is a classic of Western history and arguably the most remarkable surviving work of Anglo-Saxon literature. Obviously, the place of prestige it has come to hold throughout history has led to an intense treatment of its content by scholarship. Like many other well-acclaimed literary works, this has resulted in a plethora of variant interpretations, not only of the text’s historical and cultural influence but its very purpose. The great medievalist and fiction writer J.R.R. Tolkien played no small part in establishing the contemporary treatment of Beowulf as an intentional, carefully crafted work of art, as opposed to some accident of history, a backward and confused narrative. However, much debate remains over whether its allegiance lies in a Christian or pagan mythos.

While such debate remains relevant, a critical reader of the work need not pick exclusively between one or the other. Readers should, in a more nuanced and anthropocentric fashion, view Beowulf as a window into a medieval people group’s cultural and religious transition. Beowulf is a representation of a people group and their culture in flux and is, therefore, an expression of post-pagan, pre-Christian culture.

There are numerous explicit examples of pagan and Christian beliefs within the poem. The poet demonstrates favorability towards the idea of fate, or in the original Old English, wyrd. In the introduction to his translation, Seamus Heaney connects the term with a sense of destiny regarding Beowulf himself but also notes that its influence pervades the overall poem, for wyrd is that which is “unknowable but certain.”[1] Its overarching role in the story is indeed hard to miss. The reader encounters wyrd in numerous ways, including fate as unpredictable,[2] fate’s inevitable response to pride,[3] and violence ordained by fate.[4] Despite these portions of the text employing a fatalistic metaphysic, the poet clearly paints the old ways of paganism in an antagonistic light. The poet describes those who, in desperation to end the violence and suffering caused by monsters, returned to “pagan shrines” and “remembered hell” as “heathenish,” “forfeiting help,” with “nowhere to turn,” after thrusting their “soul in the fire’s embrace,” for the Almighty God was “unknown to them.”[5] One can clearly observe a contrast drawn between religious paganism and allegiance to what the poet depicts as the true monotheistic God.

In line with this acclaim towards “God,” the poet is favorable to certain aspects of Christian views of God’s sovereignty. King Hrothgar, described as a “good king,”[6] lists his various troubles and the pain caused by the monstrous attacks yet submits faith in God’s power over the attacks with a kind of finality in his speech.[7] Shortly before Beowulf’s battle with Grendel, the poet expresses what he implies is the clear truth that God is the final judge over every outcome.[8] Beowulf, even in glory-seeking, offers praise to God for his victory over Grendel,[9] and the poet says that Beowulf, the man, only accomplished this feat with God’s help.[10] The text is riddled with both presupposed pagan ideas and Christian sympathies. It would appear, then, that the poem is, in the words of Judith Garde, a “fairy story wrapped in an unexplicit Christian metaphysic.”[11]

Yet despite these clear references to a powerful monotheistic God, it is doubtful that the poet was exposed to more than Old Testament scripture or an orally transmitted mythos. Heaney acknowledges this possibility by noting that the poem is not so concerned with any Christian ideas of a “transcendental promise” (that is, eternal salvation) but rather identifies with the “unredeemed” temporal, more akin to concepts of justice and lack of emphasis on an afterlife in the Old Testament.[12] This Old Testament familiarity is made explicit when the medieval artist describes Grendel as one of “Cain’s clan.”[13] This idea of the various monsters being formed as a result of God’s cursing Cain is reprised throughout the work.

This is indeed significant, but the poem’s compatibility with a Christian metaphysic and the poet’s familiarity with the Old Testament doesn’t inherently prove Beowulf a fundamentally Christian work. It does not suggest that when the author refers to a monotheistic “God,” they hold a mental image of the triune God characterized by Jesus of Nazareth. John M. Hill points out that the poet doesn’t demonstrate even the basics of the Christian faith but expresses religious sentiments that align with a Christian view of God the Father.[14] Yet it is true that a work does not have to explicitly cite New Testament scripture or oral tradition to be considered a piece of Christian art. For the reader to consider the Anglo-Saxon poem as a work intentionally defined by Christian thought, the text must show even the slightest thought of New Testament ideas or theology. Jeffrey Helterman observes that the heroic, pagan tone of the work combined with the complete lack of specific Christian allusions renders reading Beowulf as a Christian text problematic.[15] It is not simply the Old Testament that makes something Christian.

Helterman addresses those who would argue that the lack of pagan gods in the story suggests it is Christian. He argues that when compared with other texts similar to Beowulf, such as Judith, Andreas, and Guthlac, the heroic poem doesn’t just exclude pagan gods but also Christ from the narrative.[16] The poet references pagan shrines yet makes no mention of sacraments or any Christian form of worship, for that matter. There are many references to a single deity, but none that would find fulfillment in anything Trinitarian or Christological in nature corresponding to orthodox Christianity. The reader finds references to eternity with God [17] but can find no concept of divine sacrifice or spiritual salvation.[18]In fact, the latter reference to eternity suggests a picture more gnostic than Christian. In some portions of the epic, the poet even gives us a picture of the divine as both pagan and monotheistic. Beowulf says, in a very Christian manner, referring to his upcoming bout, “Whichever one death fells must deem it a just judgment by God,” then later ends his speech with virtually the same message in more pagan terms, “Fate goes ever as fate must.”[19] These are not intended to be symbols posed against each other as opposites but rather forces that are mutually inclusive and working together in the same metaphysical reality.[20]

It is indeed possible that even the monotheism represented in the text is laden with a pre-conversion understanding of the singular “god.” Mary C. Wilson Tietjen suggests that Beowulf undeniably lends allegiance to elements of both pagan and Christian ideas.[21] She acknowledges the poet’s coexisting frequent usage of wyrd and clear references to a benevolent, monotheistic deity. On a surface level, even this both/and should not be entirely surprising. Germanic roots of ancient Anglo-Saxon religion knew a god-like being, a Creator figure. However, this god is limited. It is not omnipotent, omnipresent, omniscient, the God who is truly all. The Germanic concept of god (commonly known as the Aesir) is not even free from the confines of mortality; in some cases, it is still bound to wyrd. Thus, while there is a concept of “god” as a personified being, that god is still subservient to the all-consuming, non-relational force that is fate.[22] Beowulf’s particular usage of wyrd and references to God are consistent with this pre-Christian idea. In a similar fashion, Tolkien acknowledged that the text can be understood, in some ways, as “noble but heathen.”[23]

One cannot deny the elements of pagan folklore nor the elements compatible with Christian thought within the epic poem. One cannot determine if Beowulf is decidedly pagan with a hint of Christianity or explicitly Christian with some remaining paganism. The text does not offer an interpretation that is so black-and-white.

Beowulf is a poem written in the context of a group of people gradually transitioning their belief system into a monotheistic one that would eventually develop into a full and robust Christianity. Medieval multiculturalism and co-existing religious perspectives may cause difficulty in a reader’s formal analysis of the story. Yet, understanding a culture in religious transition explains the apparent conflict between pagan and Christian-adjacent theologies in the text.

Bibliography

Garde, Judith. “Christian and Folkloric Tradition in ‘Beowulf’: Death and the Dragon Episode.”

Literature and Theology 11, no. 4 (1997): 325–46. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23925523.

Beowulf: A New Verse Translation. Translated by Seamus Heaney. New York: W.W. Norton,

2000.

Helterman, Jeffrey. “Beowulf: The Archetype Enters History.” ELH 35, no. 1 (1968): 1–20.

https://doi.org/10.2307/2872333.

Hill, John M. “Beowulf, Value, and the Frame of Time,” Modern Language Quarterly, 40 (1979).

Tietjen, Mary C. Wilson. “God, Fate, and the Hero of ‘Beowulf.’” The Journal of English and

Germanic Philology 74, no. 2 (1975): 159–71. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27707876.

Tolkien, J.R.R. “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics," Proceedings of the British Academy,

12 (1936).

Weil, Susanne. “Grace under Pressure: ‘Hand-Words,’ ‘Wyrd,’ and Free Will in

‘Beowulf.’” Pacific Coast Philology, 24, no. 1/2, (1989), 94–104. https://doi.org/10.2307/1316605.

[1] Beowulf: A New Verse Translation, Seamus Heaney, trans., (New York: W.W. Norton, 2000), xvii–xix.

[2] Beowulf, trans., Heaney, 450–460.

[3] Ibid., 1200–1210.

[4] Ibid., 2070–2080.

[5] Ibid., 170–190.

[6] Ibid., 860–870.

[7] Ibid., 470–480.

[8] Ibid., 700–710.

[9] Ibid., 920–930.

[10] Ibid., 930–940.

[11] Judith Garde, “Christian and Folkloric Tradition in ‘Beowulf’: Death and the Dragon Episode,”

Literature and Theology 11, no. 4 (1997): 326.

[12] Heaney, Beowulf, xix.

[13] Ibid., 100–110.

[14] John M. Hill, “Beowulf, Value, and the Frame of Time,” Modern Language Quarterly 40, (1979): 5–7, note 8.

[15] Jeffrey Helterman, “Beowulf: The Archetype Enters History.” ELH 35, no. 1 (1968): 1.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Beowulf, trans. Heaney, 190–190, 1000–1010.

[18] Helterman discusses the problems with viewing Beowulf as a Christ figure at length in the aforementioned article.

[19] Beowulf, trans. Heaney, 440–450.

[20] Susanne Weil, “Grace under Pressure: ‘Hand-Words,’ ‘Wyrd,’ and Free Will in

‘Beowulf,’” Pacific Coast Philology, 24, no. 1/2 (1989): 94.

[21] Mary C. Wilson Tietjen, “God, Fate, and the Hero of ‘Beowulf,’” The Journal of English and

Germanic Philology 74, no. 2 (1975): 160–161.

[22] Ibid.,161–163.

[23] J.R.R. Tolkien, “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics," Proceedings of the British Academy,

12 (1936): 42.

My wife had a copy of Heaney's translation that is now buried in a mountain of other books and furniture in a storage unit. If I can brave the underworldly hazard, I'll have to dig it out and read it for the first time.

I'm curious to see how your lens might colour my reading compared to hers; she has long lauded it as a favorite, and it's high time I took the hint.

I love this! I feel like St. Justin Martyr, whose apologetic included a lot of discussion about Christianity as fulfilling all of the best in paganism, would have gone crazy about your post if he were alive today. We need more people like you talking about these kinds of things because Christ is present in a lot more of—what's left of—our common cultural values than unbelievers realize.